The Ripple Effect, Part Five: Illicit Fentanyl’s Fatal Grip On Vulnerable Communities

In the lifespan of drug use in America, fentanyl is an infant. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, before 2014, there were virtually no fentanyl-related overdose deaths. Just two years later, in 2016, it was the drug most commonly connected to overdose deaths. The illicit fentanyl crisis is particularly complex because it’s affecting a wide swath of demographics – from the person who has struggled for years with a substance use disorder to the teen experimenting with pills for the first time, to the individual seeking relief from anxiety, depression, or physical pain with a pharmacy-grade medication, only to succumb to the deception of a fake pill laced with a lethal dose of fentanyl. And although fentanyl’s impact continues to reverberate across socioeconomic, race, and gender lines, some communities are hit harder than others. In the rural Appalachian region, for example, the decline of coal mining and other industries has left many communities in economic despair. In places like Ohio, Tennessee, and West Virginia, fentanyl overdoses have become a daily occurrence, overwhelming emergency services and leaving families devastated. Similarly, in urban areas like Baltimore, Phoenix, and Sacramento, the intersection of poverty, racial inequality, and drug availability has created a perfect storm for fentanyl to take hold. This synthetic opioid, 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine, has profoundly impacted vulnerable communities that bear the brunt of the opioid crisis, exacerbating health disparities and social challenges. Understanding how and why these communities are disproportionately affected is crucial for developing effective intervention strategies.

What are vulnerable communities?

Vulnerable communities are those characterized by limited resources, economic instability, and social marginalization, which make them susceptible to poor physical, psychological, or social health. Diverse populations have inherent characteristics such as race, ethnicity, age, and sex as well as extrinsic characteristics like environment, socioeconomic status, health habits, and culture that lead to vulnerability. These communities include low-income populations, racial and ethnic minorities, rural areas, and individuals experiencing homelessness. Plus, the intersectionality of these factors – say, poverty and geographic isolation or racial minority and homelessness – means that many individuals in vulnerable communities face multiple and compounding risks, making escaping the cycle of addiction and risks of overdose even harder. We’ve broken down segments of communities, but we understand that no one demographic group – or their vulnerabilities – exists completely separate from another.

Rural areas

Historically, rural communities have been hit particularly hard by the opioid crisis, with fentanyl significantly contributing to overdose deaths. Geographic isolation, economic decline, and limited healthcare infrastructure make rural areas especially vulnerable. Residents of these areas often have to travel long distances to access addiction treatment and other healthcare services, creating additional barriers to recovery. Plus, the closure of rural hospitals and healthcare facilities has exacerbated the crisis. Rural hospitals often provide essential care for residents, but financial constraints are causing many to close. Since 2010, over 130 rural hospitals have closed. For people experiencing poverty, many of them Medicare beneficiaries, the closures are especially tough because they mean that the median travel distance to access specialized treatment, like that for substance use disorders, increases by nearly 40 miles. With fewer resources available locally, individuals struggling with addiction in rural areas may have little to no support. Additionally, the close-knit nature of rural communities can sometimes lead to stigma and reluctance to seek help, further hindering efforts to combat the crisis. The overdose rate in rural versus urban counties did begin to shift during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. In 2022, according to the CDC, rural counties had higher drug overdose rates in 8 states, including California, while urban counties had higher drug overdose death rates in 23 states.

Economically-disadvantaged populations

Low-income individuals, both rural and urban, often face a slew of challenges that increase their vulnerability to the ravages of fentanyl. Starting around 2010, doctors notoriously over-prescribed opioid pills, especially in lower-income, White communities. As restrictions on opioid prescriptions increased, the use of heroin – and then the cheaper alternative, fentanyl – increased as more affordable but deadly substances. Regardless of race, economic instability can lead to chronic stress, mental health issues, and limited access to healthcare, making drug use a coping mechanism for some. In areas plagued by poverty, the prevalence and potency of fentanyl can quickly turn occasional drug use into a serious substance use disorder.

In communities with high poverty and lack of economic investment, intergenerational substance misuse, along with selling drugs, can be common and a source of economic survival, creating a vicious cycle of addiction and relapse that becomes difficult to change. Financial constraints also mean that low-income individuals may not be able to afford comprehensive addiction treatment, assuming there are even treatment options available. Public healthcare systems, often underfunded and overstretched, struggle to meet the needs of these populations.

BIPOC Communities

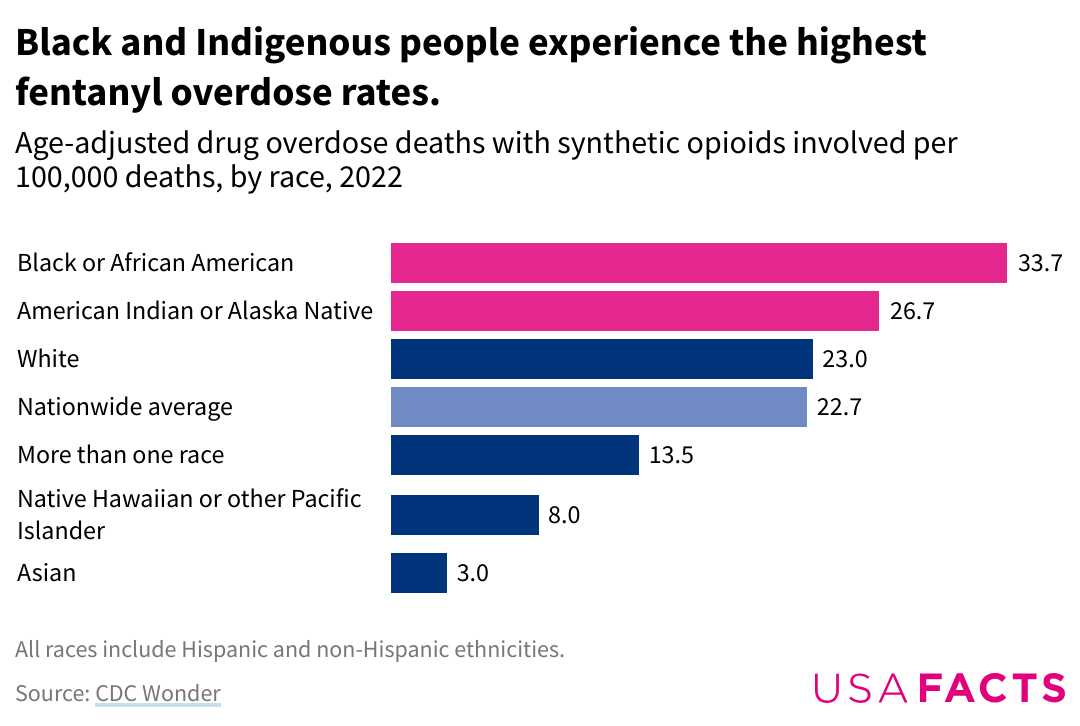

Communities of color, particularly Black and Indigenous, are disproportionately affected by the fentanyl crisis. Historical trauma and systemic inequalities have resulted in these communities facing higher rates of poverty, fewer overall resources, limited access to quality education, healthcare, and treatment options, and increased exposure to environments where drug use is more prevalent. New research from Penn State indicates a shift in who is most at risk from the opioid crisis that continues to wreak havoc across the nation. From 2010-2019, the opioid epidemic was considered mainly a problem for rural White America, with White individuals twice as likely to die from overdose. However, by mid-2021, the highest drug overdose death rates were among American Indian or Alaska Native men aged 15 to 34 years and Black and American Indian or Alaska Native men aged 35 to 64 years. In 2020 alone, according to researchers at the University of California Los Angeles, the death rate increased among Black and Indigenous Americans by 49% and 43% in just one year. Likewise, overdose rates among Latinos have nearly tripled since 2011, according to a report in the American Journal of Epidemiology, with the majority of the deaths from polysubstance use, where fentanyl is mixed with other drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine.

Discrimination and bias within the healthcare system further exacerbate the issue. Minority individuals may receive lower-quality care, experience delays in treatment and inequitable drug prescribing practices, or face stigma when seeking help for substance abuse. These barriers can lead to higher overdose rates and lower recovery rates in minority communities. An example of a barrier related to prescribing practices is the reduced likelihood that Black patients receive prescribed buprenorphine, a synthetic opioid developed in the late 1960s used to treat opioid use disorder. Research indicates that, in 2020, Black Americans who experienced a fatal overdose were about half as likely to have had medication substance use treatment, such as with buprenorphine, compared with White Americans. Similarly, pharmaceutical companies agreed to a $590m settlement with Indigenous American tribes over claims that sales of opioid pills, such as Oxycontin, targeted Native communities and led to a marked increase in levels of addiction and overdose deaths.

Homeless populations

The homeless population is another group that faces extreme vulnerability to fentanyl, especially during and after the COVID-19 pandemic, when the demographic experienced an increase in deaths during the first year of the pandemic. Though chronic health issues remain the number one cause of death, according to Bobby Watts, chief executive at the nonprofit National Health Care for the Homeless Council, substance use is a significant contributor to an increase.

Homelessness often stems from a combination of factors, including economic hardship, mental health issues, and substance misuse and abuse. A lack of health insurance, coupled with struggles with behavioral health issues, creates barriers that can feel insurmountable and increases the risk of experiencing homelessness. According to the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, approximately 653,000 people in America experienced homelessness in 2023, with 1 in 5 struggling with a mental health issue.

For those living on the streets, the risk of encountering fentanyl-laced drugs is high, and the lack of stable housing complicates efforts to manage addiction and seek treatment. Individuals experiencing homelessness often lack access to basic healthcare and addiction services. Even when services are available, the transient nature of homelessness makes consistent outreach and treatment challenging.

LGBTQ+ communities

The National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) reports that LGB adults have almost three times greater risk of an opioid use disorder as compared to heterosexual adults. While we know that transgender adults are four times as likely to experience a substance use disorder (SUD), data that offers detailed insight into the degree of substance use disorders and overdoses experienced by individuals in the LBGTQ+ community are limited, especially for transgender people. Minority stress, including stigma and discrimination experienced in healthcare settings, struggles with mental health, suicide ideation, and bullying, along with rejection from family, friends, and society, increase the risks for LGBTQ+ people, as individuals may turn to substance use to cope with these significant stressors. A study published in the Journal for Substance Abuse Treatment found a notable gap in the number of opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment facilities offering LGBTQ-specific services compared to the number of individuals in need of such care.

Pregnant women

Opioid misuse during pregnancy is linked with serious adverse health outcomes for pregnant women and developing fetuses. Fentanyl can be mixed with many different types of drugs to create dangerous combinations, which makes the effects on the mother and developing fetus unpredictable. These drugs also can interfere with healthy growth and development, causing miscarriage or preterm delivery. The baby may be born too small or too early, which makes it more likely it will need to be cared for in the newborn intensive care unit (NICU). Babies can experience withdrawal – neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) – from drugs, particularly opioids, showing symptoms such as irritability, crying, poor sleep habits, poor feeding, tremors, seizures, vomiting, and diarrhea. Stimulant drugs like cocaine and methamphetamine and other narcotics like opioids, including fentanyl, may interfere with the growth of the brain before the baby is born, leading to neurodevelopmental delays that can present as long-term behavioral and learning challenges.

Intersectionality Compounds Challenges

Addressing the fentanyl crisis in these communities requires a nuanced understanding of intersecting factors. Often, a person’s lived experience is impacted by challenges they face as part of more than one vulnerable community. Take Brisa, for example.

Years of struggle with an undiagnosed bipolar disorder led to self-medication with illicit drugs. Brisa didn’t feel comfortable talking about her mental health challenges during her teen years. Such topics felt taboo in her family, and she feared she’d be a burden – that seeing a doctor would put a financial strain on her mom. She began self-medicating with drugs in high school, which then led to a substance use disorder and a falling out with her family. Her ongoing substance use made keeping a job for a prolonged period difficult, and soon, Brisa found herself couch-surfing and then finally living in temporary shelters or on the street.

This intersection of homelessness, mental health struggles, and the stigma Brisa feels as part of her family and cultural community creates a complex issue that is not unique to her story, unfortunately. Black and Latino groups are historically overrepresented in poverty. For example, in 2023, Black Americans represented 13 percent of the general population but 37 percent of individuals experiencing homelessness.

Likewise, polysubstance use and intergenerational substance use are not uncommon, especially in historically underserved and disadvantaged communities where poverty and lack of resources make daily living difficult for people. Often, substance misuse is passed from one generation to the next, creating a cycle of struggle with substance use disorder that can be very difficult to break free from. Efforts must be tailored to address each individual's specific challenges, taking into account the broader social and economic context in which they live.

Social and Economic Consequences

The social repercussions of fentanyl abuse are troubling. Families are torn apart as loved ones succumb to addiction or overdose. Communities face increased crime rates as individuals struggling with addiction may, in desperation, turn to illegal activities to support their drug use. This, in turn, creates a cycle of poverty and instability, making it even harder for these communities to recover.

Public health systems are struggling to cope with the influx of fentanyl-related cases. Emergency departments, addiction treatment centers, and harm reduction programs are all experiencing increased demand, stretching their resources thin. Economically, the burden is immense. The cost of healthcare, lost productivity, and law enforcement efforts to combat fentanyl distribution all add up. According to a study by the American Action Forum, the opioid crisis has cost the U.S. economy over $1 trillion since 2001, with fentanyl playing a significant role in recent years.

Future Outlook

The future of fentanyl use and its impact on vulnerable communities remains uncertain. The devastating health, social, and economic consequences highlight the urgent need for continued awareness, support, and action. While significant strides have been made in addressing the crisis, ongoing efforts are necessary to sustain progress. Innovations in treatment, investment in prevention and awareness, and policy changes could further alleviate the burden on vulnerable communities. More community-based programs, many highly innovative, are emerging, drawing on the expertise and empathy of local people working to build relationships in these diverse communities. There is no shortage of people dedicated to working to end the opioid crisis – and the broader issues of substance use and addiction. By understanding communities’ challenges and implementing effective strategies, we can work towards a future where the grip of fentanyl is loosened and hope is restored.

References

Allen, Cassandra. (2023, May). IHS supports tribal communities in addressing the fentanyl crisis. Indian Health Service. https://www.ihs.gov/newsroom/ihs-blog/may-2023-blogs/ihs-supports-tribal-communities-in-addressing-the-fentanyl-crisis/#:~:text=In%202022%2C%20the%20CDC%20reported,56.6%20deaths%20per%20100%2C000%20persons

California Hospital Association. (2024, April 18). California’s rural communities at risk. https://calhospital.org/issue-brief-rural-health-care/

Fentanyl. (2023, July). National Library of Medicine; Organization of Teratology Information Specialists (OTIS). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK582701/

Han, B., Einstein, E. B., Jones, C. M., Cotto, J., Compton, W. M., Volkow, N.D. (2022). Racial and ethnic disparities in drug overdose deaths in the US during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 5(9):e2232314. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.32314

James, K., Jordan, A. (2018). The opioid crisis in Black communities. Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 46(2):404-421. doi:10.1177/1073110518782949

Jimenez, J. (2023, March 23). Drug overdose deaths among Latinos have nearly tripled in the past decade. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/drug-overdose-deaths-latinos-almost-tripled-decade-rcna76315

Jones, A. A., Waghmare, S. A., Segel, J.E., Harrison, E. D., Apsley, H. B., Santos-Lozada, AR. (2024). Regional differences in fatal drug overdose deaths among Black and White individuals in the United States, 2012-2021. Am J Addict., 1-9. doi:10.1111/ajad.13536

Kamp, J., & Frosch, D. (2023, March 27). Fentanyl fuels surge in deaths among those who are homeless. Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/fentanyl-fuels-surge-in-deaths-among-those-who-are-homeless-6490366a.

Mahr, K. (2023, May 3). For Black Americans, the pandemic spike in fentanyl deaths was decades in the making. Politico. https://www.politico.com/news/2023/05/03/covid-19-inflamed-the-opioid-crisis-particularly-for-black-americans-00095006

McCormick, E. (2022, February 17). “Historically tragic”: Why are drug overdoses rising among Black and Indigenous Americans? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/feb/17/black-native-americans-fentanyl-deaths-rise-opioid-crisis

McCormick, E. (2022, April 23). The daily battle to keep people alive as fentanyl ravages San Francisco’s tenderloin. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2022/apr/23/san-francisco-homelessness-street-team-fentanyl.

Moazen-Zadeh, E., Karamouzian, M., Kia, H., Salway, T., Ferlatte, O., & Knight, R. (2019). A call for action on overdose among LGBTQ people in North America. The Lancet Psychiatry, 6(9), 725–726. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(19)30279-2

National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2023, December 18). Homelessness and racial disparities. https://endhomelessness.org/homelessness-in-america/what-causes-homelessness/inequality/#:~:text=The%20most%20striking%20disparity%20can,has%20not%20improved%20over%20time

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2024, May 14). Drug overdose death rates. National Institute on Drug Abuse; National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/trends-statistics/overdose-death-rates

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2021). Opioid overdose crisis. https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/opioids/opioid-overdose-crisis

National LGBT Health Education Center. (2018). Addressing opioid use disorder among LGBTQ populations. Fenway Institute. https://www.lgbtqiahealtheducation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/OpioidUseAmongLGBTQPopulations.pdf

Niamatullah, S., Auchincloss, A., Livengood, K. (2022). Drug overdose deaths in big cities. Drexel University, Urban Health Collaborative. https://drexel.edu/uhc/resources/briefs/BCHC%20Drug%20Overdose/

O'Donnell, J. K., Halpin, J., Mattson, C. L., Goldberger, B. A., & Gladden, R. M. (2017). Deaths involving fentanyl, fentanyl analogs, and U-47700—10 states, July–December 2016. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 66(43), 1197. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6643e1

Paschen-Wolff, M. M., DeSousa, A., Emily Allen Paine, Hughes, T. L., & Aimee N.C. Campbell. (2024). Experiences of and recommendations for LGBTQ+-affirming substance use services: an exploratory qualitative descriptive study with LGBTQ+ people who use opioids and other drugs. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00581-8

Paschen-Wolff, M. M., DeSousa, A., Emily Allen Paine, Hughes, T. L., & Aimee N.C. Campbell. (2024). Experiences of and recommendations for LGBTQ+-affirming substance use services: an exploratory qualitative descriptive study with LGBTQ+ people who use opioids and other drugs. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13011-023-00581-8

Pierce, M., Hayhurst, K., Bird, S. M., Hickman, M., Seddon, T., Dunn, G., Millar, T. (2017, Oct 1). Insights into the link between drug use and criminality: Lifetime offending of criminally-active opiate users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 179:309-316. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.07.024.

SAMHSA. The opioid crisis and the Black/African American population. (n.d.). https://store.samhsa.gov/sites/default/files/pep20-05-02-001.pdf

Spencer, M. R., Warner, M., Cisewski, J. A., Miniño, A., Dodds, D., Perera, J., & Ahmad, F. (2023, May). Estimates of drug overdose deaths involving fentanyl, methamphetamine, cocaine, heroin, and oxycodone: United States, 2021. NVSS Vital Statistics Rapid Release. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/vsrr/vsrr027.pdf

Spencer, M. R., Garnett, M. F., Miniño, A. M. (2022). Urban-rural differences in drug overdose death rates, 2020. NCHS Data Brief, no 440. National Center for Health Statistics. DOI: https://dx.doi. org/10.15620/cdc:118601.

Texas Epidemic Public Health Institute. (n.d.). Vulnerable populations. https://tephi.texas.gov/docs/tephi-who-are-vulnerable-populations.pdf?language_id=1

Townsend T., Kline D., Rivera-Aguirre A., Bunting, A.M., Mauro, P.M., Marshall, B.D.L., Marins, S.S., Cerda, M. (2022, Mar). Racial/Ethnic and Geographic Trends in Combined Stimulant/Opioid Overdoses, 2007-2019. American Journal of Epidemiology, 191(4):599-612. DOI: 10.1093/aje/kwab290.

USAFacts. (2024, May 28). Who is overdosing on Fentanyl? https://usafacts.org/articles/who-is-overdosing-on-fentanyl/

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2024, July 30). “To walk in the beauty way”: Treating opioid use disorder in native communities. National Institutes of Health. https://heal.nih.gov/news/stories/native-cultures

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). HUD 2023 continuum of care homeless assistance programs homeless populations and subpopulations. https://files.hudexchange.info/reports/published/CoC_PopSub_NatlTerrDC_2023.pdf.

Wagner, A. (2024, April 30). Fentanyl and COVID-19 pandemic reshaped racial profile of overdose deaths in US. Penn State University. https://www.psu.edu/news/health-and-human-development/story/fentanyl-and-covid-19-pandemic-reshaped-racial-profile-overdose/