The Ripple Effect, Part Four: Borders to Bedrooms – Illicit Fentanyl’s Path Into Communities

“My daughter went unconscious on her grandmother’s bed for 38 minutes.” After taking a pill laced with fentanyl, Owen Newman’s daughter, Talaia, was unconscious for 38 minutes before 911 was called. She fought for eight days before succumbing to her body’s response to fentanyl poisoning. Owen’s eyes fill with tears as he describes taking her off of life support and as he reflects on the life events he will miss – walking her down the aisle, playing with a grandchild. He’s determined to use Talaia’s story to raise awareness about the dangers of illicit fentanyl so that other parents don’t have to experience the immense loss that haunts him every day.

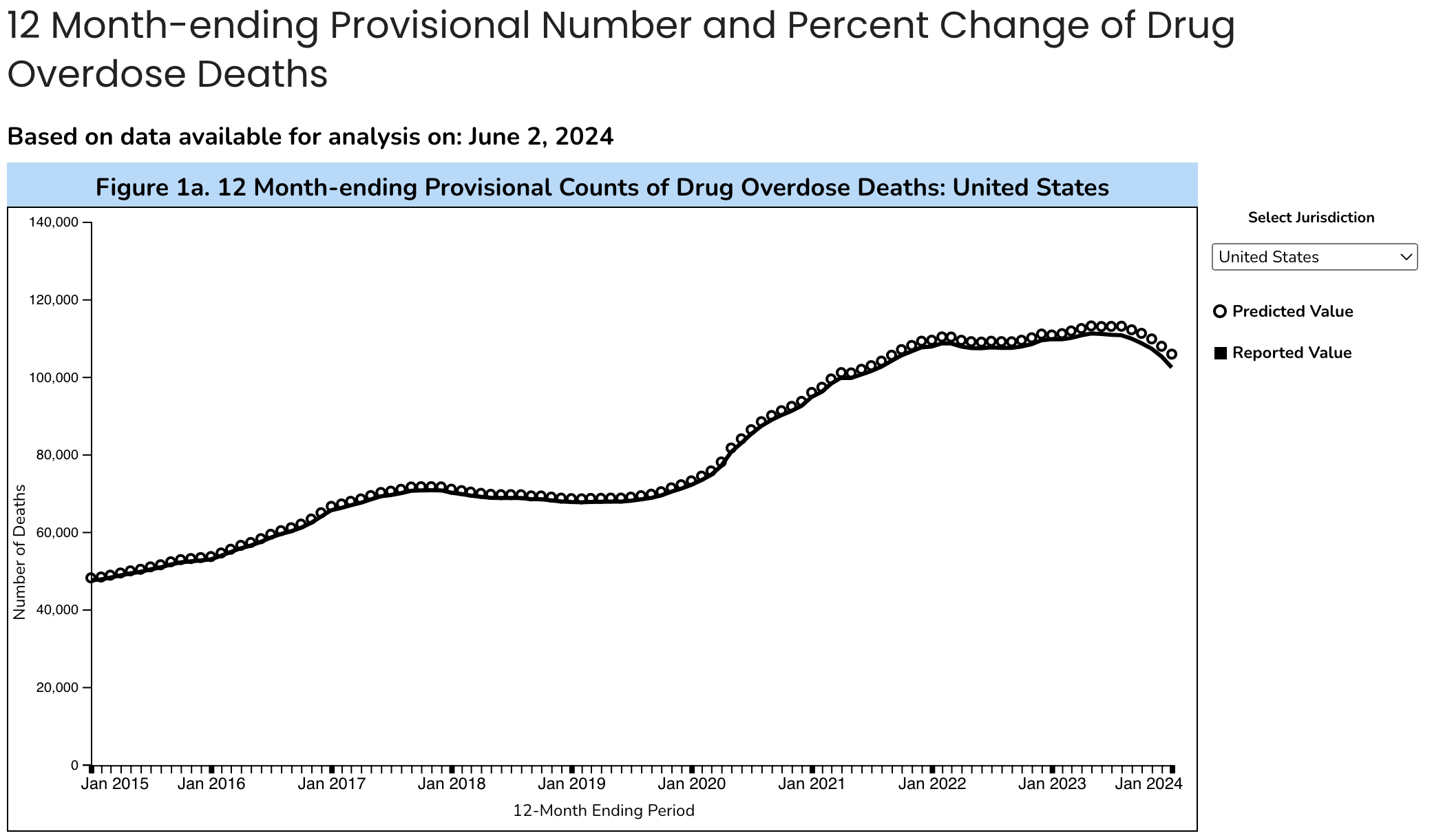

Recent numbers from the CDC show the number of overdose deaths in the country has slightly decreased for the first time in five years, with a 4% national decline in fentanyl-related deaths. Yes, these numbers are hopeful, but overall rates are still exceedingly high. According to a report published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, local law enforcement seized more than 115 million pills containing fentanyl in 2023. For perspective, that was more than double the 49 million seized just six years earlier in 2017. According to the DEA, in 2021, four out of every ten fake prescription pills contained potentially lethal amounts of fentanyl. That number rose to seven out of ten in 2023, prompting a public safety alert. The most recent DEA numbers indicate the number has dropped to 5 out of 10. This is good news, but 50% is still much too high.

Source: www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

Initially developed for pain management, fentanyl’s illicit production and distribution have skyrocketed, leading to widespread misuse and a sharp increase in overdose deaths in communities across the nation over the last decade. In the previous installment of our documentary blog series, The Ripple Effect, we examined how illicit fentanyl crosses U.S. borders and the countermeasures taken by various government agencies. But once the fentanyl crosses our borders, how does it make its way onto our neighborhood streets and into our loved ones’ pockets and bedrooms?

Distribution Networks

As explained in our last blog post, the backbone of illicit fentanyl distribution in the United States is formed by transnational crime organizations (TCOs) such as Mexican cartels, primarily the Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation cartels (CJNG). These organizations are highly sophisticated, operating with a level of efficiency comparable to multinational corporations, and they are about one thing: their bottom line.

Most often, fentanyl powder is used to adulterate, or cut, other substances such as cocaine, heroin, meth, and ecstasy, making them more addictive and cheaper to manufacture. Increasingly, fentanyl is used to produce counterfeit prescription pills that mimic Xanax, Adderall, Percocet, and, Oxycontin. Many of these fake “fentapills” are made to resemble the blue, round prescription oxycodone pills; they are even stamped with the “M” on one side and the “30” on the other. The counterfeit “M30s” often contain NO oxycodone – instead, they are pure fentanyl and filler.

The TCOs control all aspects of fentanyl trafficking, from production to distribution, ensuring that their product reaches every corner of the United States. After entering the United States, fentanyl is distributed to regional cells across the country. These cells act as intermediaries, receiving bulk shipments from the cartels and distributing smaller quantities to their associates and brokers. The regional cells are responsible for breaking down large shipments into smaller, more manageable quantities, which are then transported to various urban and rural areas using the nation’s physical and digital infrastructure.

The I-5 Corridor

The interstate highway system is a critical infrastructure for the national distribution of fentanyl, serving as the primary artery for the transportation of fentanyl across the country. In the West, the I-5 Corridor is the main thoroughfare that allows for the transportation of goods and, unfortunately, enables fentanyl to seep into the region. This 1,381-mile-long corridor runs from the Mexican border in San Diego through California and Oregon to the Canadian border in Washington, passing through major metropolitan areas including Seattle, Portland, Sacramento, Los Angeles, and San Diego. California, with its vast population and extensive coastline, is a critical entry point for fentanyl into the United States. The corridor is heavily utilized for the smuggling and distribution of illicit fentanyl, with key hubs along the route serving as major distribution points. Not only do distributors capitalize on the major cities along Interstate 5, but the I-5 corridor also provides easy access to numerous rural and suburban areas between the major urban centers. These areas, which may have fewer law enforcement resources and lower public awareness about the opioid crisis, are increasingly targeted by traffickers seeking to expand their markets.

Smugglers use various tactics to move their products along the I-5 corridor and other highway networks throughout the United States. One method is concealment in both passenger and commercial vehicles. Traffickers use sophisticated methods to hide the drugs in areas such as engine compartments, dashboards, and seats to evade detection by law enforcement at checkpoints and border crossings. The sheer volume of traffic on I-5 makes inspecting every vehicle thoroughly difficult for law enforcement. Both passenger vehicles and commercial trucks move in vast numbers, providing cover for traffickers who blend in with legitimate traffic. Given the high volume of commercial traffic on I-5, traffickers frequently use trucks to transport large quantities of fentanyl. The drugs are hidden among legitimate cargo – from powdered soap to fresh green beans – making detection more challenging. Plus, because the interstate spans three states, effective enforcement requires extensive coordination efforts among local, state, and federal agencies.

Urban Hubs

Major cities across the United States serve as central hubs for the distribution of fentanyl. These urban centers provide dense populations and extensive transportation networks, making them ideal locations for drug trafficking operations. Once fentanyl reaches regional and urban hubs, it is further distributed to local communities. All three West Coast states – Washington, Oregon, and California – continue to grapple with the opioid crisis, but we will begin to narrow our focus to California. Once fentanyl enters California, it’s distributed throughout the state using a combination of regional hubs, local networks, and major transportation routes. Given its proximity to the Mexican border and major ports, San Diego is both an entry point and a distribution hub. Fentanyl entering through land border crossings is distributed within the city and north to other parts of California. Los Angeles and San Francisco serve as primary distribution hubs for fentanyl within California as well. The cities’ extensive transportation networks, including major highways and airports, large populations, and bustling economic activity facilitate the efficient movement of fentanyl to other cities throughout the state, like San Jose. Sacramento also plays a role in the distribution network as the state capital. Its location along major highways, such as I-5 and I-80, makes it a convenient transit point for fentanyl transported to Northern California and neighboring states. Just last month, on May 28th, Governor Gavin Newsom’s office issued a press release announcing that the state’s Counterdrug Task Force, in partnership with law enforcement, seized more than 5.8 million pills containing fentanyl from January to April 2024. As a result, he is “more than doubling the California National Guard’s (Cal Guard) Counter Drug Task Force operations statewide, including at ports of entry along the border from 155 to now nearly 400 service members.”

Though major cities play a key role in fentanyl distribution, we do need to understand that it is not limited to major cities. Smaller towns and rural areas throughout the U.S. have seen an increase in fentanyl availability. In fact, according to the CDC, in five states, including California, the rate of drug overdose deaths in rural counties in 2021 was higher than those in urban counties. Local gangs and independent dealers, often connected to larger drug-trafficking organizations, are responsible for distributing fentanyl in these areas. The spread of fentanyl to rural and suburban communities highlights the pervasive nature of the opioid crisis and the vast reach of trafficking networks.

Local Distribution

Once fentanyl makes its way from borders into urban hubs and smaller cities and towns, it’s further distributed and sold to the end consumers: brothers, daughters, cousins, best friends, coworkers. This is the point in fentanyl’s insidious journey where we begin to really see and understand the human impact – the loved ones lost and the ripples of grief, frustration, and anger that follow.

Local gangs play a crucial role in the street-level distribution of fentanyl. They control specific territories and are responsible for distributing the drug to users within their areas of influence. They typically coordinate with transnational crime organizations (TCOs) and drug trafficking organizations (DTOs) to move drugs into communities. In many urban areas, open-air drug markets facilitate the sale of drugs, including fentanyl. These markets are typically controlled by gangs and provide a centralized location for people to purchase the drugs. In addition to gangs, independent dealers operate within local communities, selling fentanyl directly to individuals. These dealers often source their supply from regional distributors or dark web marketplaces. People who seek out illegal drugs may find local dealers through mutual friends or acquaintances, connecting through text messaging to arrange logistics to secure the deal.

The Role of Tech

Technology significantly impacts the distribution of fentanyl throughout the country, including California. Both the clear (standard browser, like Google) and dark web make purchasing drugs more accessible for the masses and are appealing because buying online offers more anonymity. People can order and pay for substances like illicit fentanyl through web transactions and receive drug deliveries directly to their homes by standard mail or express consignment services such as UPS or FedEx. Purchasing drugs using cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin, provides an additional layer of anonymity and makes tracing financial transactions difficult for law enforcement. Drug dealers capitalize on the rapid development and constant flux in encrypted messaging apps, social media platforms, and e-commerce to entice buyers, increase profit margins, and elude detection.

Buying something like Adderall or Percocet online is as easy as scrolling through Snapchat, TikTok, Instagram, or other social media platforms and encountering advertisements that use code words and emojis to market illicit drugs. After connecting on social media, the buyer and dealer typically move to encrypted messaging apps like WhatsApp, payment is made using apps like Venmo, Zelle, and Cash App, and a meetup is arranged. While individuals looking to buy illegal drugs seek out such advertisements, these drug dealers also prey on young adults and teens who spend a lot of their time scrolling on social media and are considering experimenting with substances. We will further explore the impact of illicit fentanyl on our youth, specifically, in a future blog installment.

Moving Forward

It’s true that the distribution of fentanyl throughout the United States and within California is complex and, at times, may feel insurmountable as drug traffickers constantly alter methods to thwart detection, leading to devastating numbers of overdose and poisoning deaths on our streets and in our homes. We must maintain hope that continuing efforts to coordinate with federal, state, and community-level organizations and working to develop effective strategies to treat substance use disorders and prevent fentanyl poisoning will save lives. In our next blog installment, we will spend more time seeking to understand the impact of fentanyl on different groups of people – rural populations, communities of color, youth populations, LGBTQ+, Native, and homeless communities. Though fentanyl does not discriminate, not all communities are impacted in the same way. Please join us as we continue our documentary blog series, The Ripple Effect.

References

California Department of Public Health. (2021). California opioid overdose surveillance dashboard. https://skylab.cdph.ca.gov/ODdash/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024, June 12). Provisional drug overdose death counts. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nvss/vsrr/drug-overdose-data.htm

Drug Enforcement Administration. (2021). Fentanyl flow to the United States. U.S. Department of Justice. https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-11/DEA_Fentanyl_Flow_Report_2021.pdf

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2021). Fentanyl drug facts. National Institutes of Health. https://nida.nih.gov/publications/drugfacts/fentanyl

Office of Governor Gavin Newsom. (2024, June 17). Governor Newsom more than doubles deployment of California National Guard to crack down on fentanyl smuggling. https://www.gov.ca.gov/2024/06/13/governor-newsom-more-than-doubles-deployment-of-california-national-guard-to-crack-down-on-fentanyl-smuggling/

One pill can kill. DEA. (n.d.). https://www.dea.gov/onepill#:~:text=Laboratory%20testing%20indicates%207%20out,a%20lethal%20dose%20of%20fentanyl

Palamar, J. J., Fitzgerald, N. F., Carr, T. H., Cottler, L. B., & Ciccarone, D. (2024). National and regional trends in fentanyl seizures in the United States, 2017–2023. International Journal of Drug Policy. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2024.104417.

RAND Corporation. (2019). The future of fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR3117.html

Solis, N. (2024, February 28). California seized enough fentanyl last year to kill everyone in the world “nearly twice over.” Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2024-02-27/california-record-fentanyl-seizures

U.S. Department of Justice, DEA. (2022). 2020 National drug threat assessment (NDTA). https://www.dea.gov/sites/default/files/2021-02/DIR-008-21 2020 National Drug Threat Assessment_WEB.pdf

The White House: Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2022). National interdiction command and control plan. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/2022-National-Interdiction-Command-and-Control-Plan-NICCP.pdf